Photographing a Single Atom

When I spent one Sunday night working on a photograph in our basement laboratory last August, I was admittedly quite pleased with the results. But I certainly didn’t expect the attention it recently received from news media around the globe after winning an award in a photography competition. In this post, I will try to provide some of the scientific background sorely missing from the original press release, and address a few commonly asked questions.

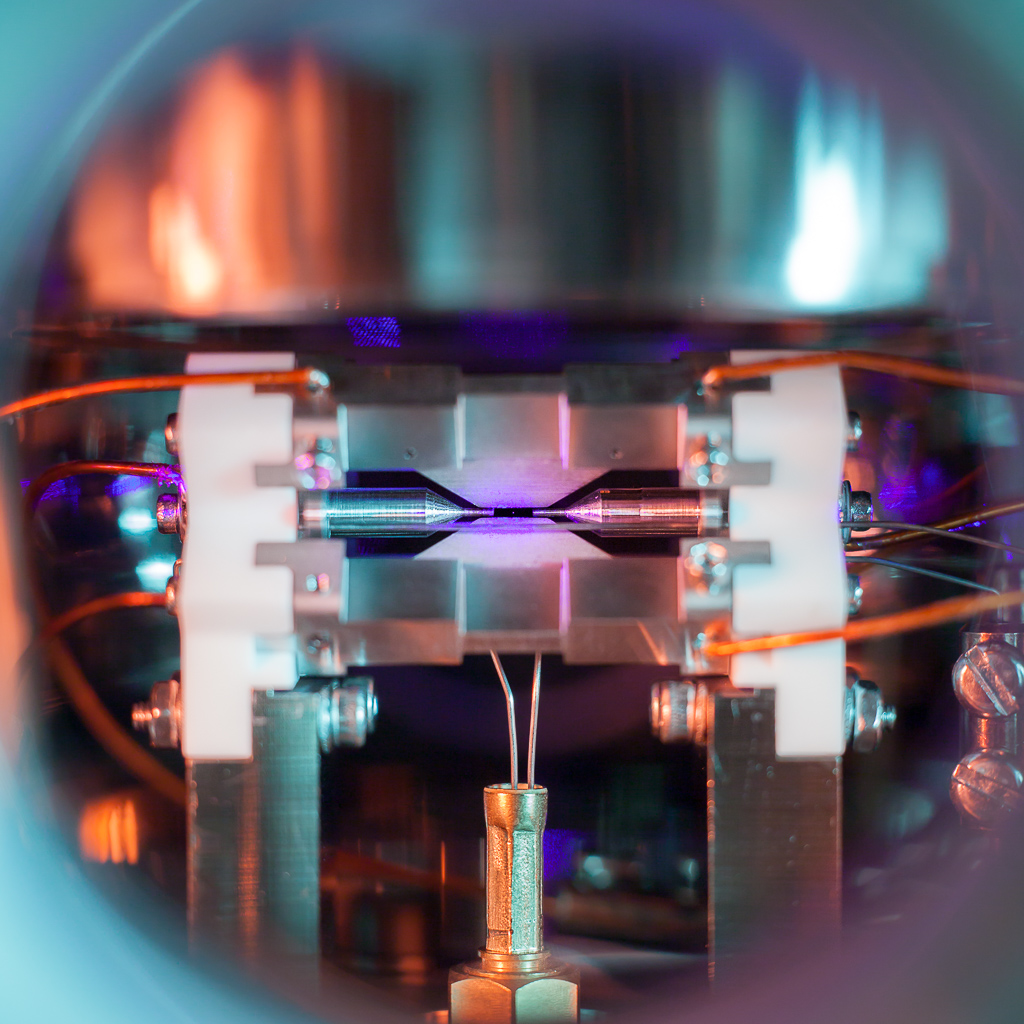

First of all, another look at the picture in question, taken on August 7, 2017, at 2:36 AM in the laboratories of the Ion Trap Quantum Computing group (Prof. David Lucas and Prof. Andrew Steane) at the University of Oxford. As part of my DPhil studies at Balliol College, I work on using ion traps for quantum computation, in particular towards distributing high-fidelity entanglement between several trap modules using optical links (click for a high-quality version, 4.1 MiB):

Before getting into the details of the science behind all this, one particular misconception that has cropped up in the search for sensationalist headlines should be addressed:

Is this an advance in science? Have single atoms been photographed before?

In short: Not in the least; and yes, probably even before I was born.

First, the techniques that made this picture possible, ion traps and laser cooling, are part of the standard toolbox in modern physics experiments. The photo could have been taken in dozens—if not hundreds—of laboratories around the world, with any one of more than ten different species of atoms. To be very clear, the picture won a photography competition, not a science prize.

Nevertheless, the picture still showcases a lot of cool innovations in physics and engineering from the second half of the 20th century. To name just a few highlights—telling a scientific story in Nobel prizes necessarily paints a very incomplete picture: Both the aforementioned experimental techniques were recognized with the prestigious prize, ion traps in 1989, and the application of laser cooling to neutral atoms in 1997. In 2012, D. Wineland was awarded the Nobel prize for the development of methods to precisely manipulate the quantum state of trapped ions. This is the basis for a number of research groups around the world to investigate them as building blocks for quantum information applications, including ours.

On the second point, this is nowhere near the first picture of a single atom, probably by almost as much as forty years—I can’t help but think that someone working on the early ion trap experiments would have tried to take such a picture as well. Either way, taking pictures of single atoms has been a part of our experiments for a good ten years now, as a way of reading out the result of a quantum computation from our ion qubits (arXiv)—the result in 0s and 1s is literally given as a pattern of bright dots and spots that stay dark. For another example, check out the second picture on our group website, showing a string of 43Ca+ ions.

Neutral (uncharged) atoms can also be trapped using laser techniques. People have taken pictures of single atoms in this setting too, such as this group in Otago, New Zealand. Like the pictures used for ion qubit readout, these are typically taken with scientific cameras (lower noise, but usually monochrome) and through a microscope with narrow field of view. By using an ordinary camera, I was able to capture a picture in full colour, including more of the surrounding apparatus.

There is also this funny—possibly apocryphal—story from the early days of ion trapping, featuring a group around Hans Dehmelt (one of the above Nobel laureates) and a photo of a single Barium atom they took back in the very much analogue age of photography: Supposedly, their picture was mostly black, with only a few small bright spots from the ion itself and a bit of stray light hitting the trap electrodes. When they submitted the negatives for publication in some conference proceedings, the image editor promptly stamped out the atom, thinking it to be a speck of dust!

All in all, the scientific value of this image is virtually zero. Still, I hope it can convey some of the fascinating aspects of nature we get to explore in modern physics on a daily basis.

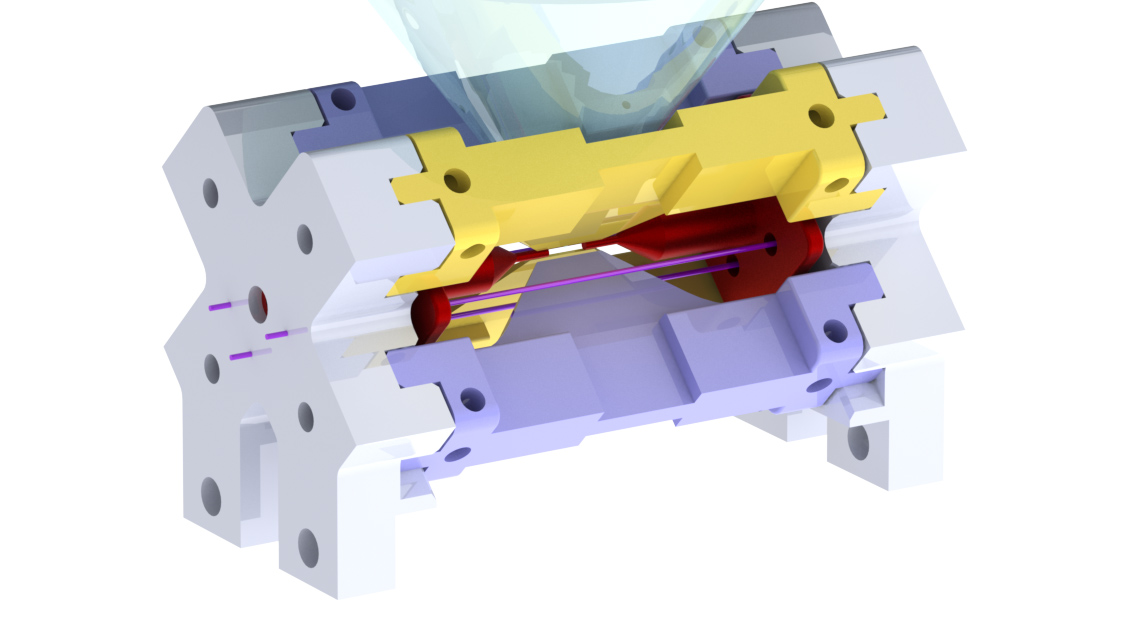

The rest of this blog post is work in progress. For now, have a look at this 3D model of our trap, where the individual parts are easier to recognise than in the picture:

Colleagues of ours, the group around Rainer Blatt in Innsbruck, have a few more pictures of similar traps on their website.

A collection of some further links:

-

Seeing a single atom in person is possible with a magnifying glass or a small microscope, as discussed in this New York Times article from 1986. Apparently, this has been done even back in 1979.

-

The radius of an atom is a bit tricky to define; according to one common definition (the space taken up in a molecular bond to another atom of the same species), the radius of the strontium atom is about 0.25 nm (a quarter of a billionth of a metre). When confined in a trap potential with frequency \(\omega\), its size is at least \(z_0 = \sqrt{\hbar / (2\ m_{Sr}\ \omega)}\) due to the Heisenberg uncertainty principle. For the trap parameters here, the radius is about 6.5 nm. This is far below the diffraction limit set by the light wavelength of 422 nm.

-

The temperature of the atom is approximately 0.5 mK, or 1 / 2 000 ºC above absolute zero (slightly above the Doppler limit). Hence, the size due to “motion blur” would still be less than 300 nanometres.

-

The atom appears bigger due to imperfection in the lens and camera (optical aberrations, plus the focus is slightly off). There seems to be a small amount of camera shake as well (the camera was mounted to the optical table in a somewhat precarious fashion using a cheap tripod head).

-

Since ions repel each other, one can take pretty pictures of interesting configurations of glowing atoms using a microscope. See for example our group website, or the much fancier pictures by the groups at PTB Braunschweig and NIST Boulder.

-

The photo was captured on August 7th, 2017, with a Canon EOS 5D Mark II and an EF 50 mm f/1.8 lens at 30s exposure time and f/4 (plus some extension tubes, and two flash units with colour gels).

-

The quantum efficiency and noise performance of modern digital camera sensors is surprisingly good. Roger N. Clark has collected a swath of useful information over at his website, see for example his page on the camera I used, and his overview of modern digital camera sensor performance. The Sensorgen.info and Photons to Photos websites also provide further information and data on sensor performance. In fact, it appears that if I had taken a closer look at the performance data before I took the picture, I could have optimised the settings a bit more to reduce the apparent noise.

[A long-form blog post is work in progress.]