D/Thrift: Non-Blocking Server, Async Client, and more

First of all, the usual apologies for publishing this post later than I originally planned to. No, seriously, drafting a solid asynchronous client implementation ended up being a lot more work than I originally anticipated, but I wanted to discuss my ideas in this status report. Now, the post turned out way too large anyway, but I guess that’s what I deserve. ;)

Also, a quick notice beforehand: A week ago, DMD 2.054 was released. It is the first version to include, amongst a wealth of other improvements, Don’s necessary CTFE fixes and my std.socket additions. This means that it is no longer necessary to use a Git build to use Thrift with D, you can just go to digitalmars.com and fetch the latest package for your OS.

Small but useful additions

But before discussing the intricacies of non-blocking I/O, to the mundane helper transports that found their way into the D library: The first addition was a simple TInputRangeTransport which, as the name says, just reads data from a generic ubyte input range, with some optimizations for the case where the source is a plain ubyte[] (std.algorithm.put is currently unnecessarily slow if both ranges are sliceable, I didn’t have time to prepare a fix for Phobos yet). It can e.g. be used in cases where want to deserialize some data from a memory buffer, and don’t need to write anything back (which is where TMemoryBuffer would be used).

Another addition is TZlibTransport, which wraps another transport to compress (deflate) data before writing it to the underlying transport, and decompress (inflate) it after reading. This is implemented by directly using zlib (via the C interface) instead of using std.zlib, because the API of the latter would have made it impossible to avoid needlessly allocating buffers all the time. Thankfully, the C++ library already included a zlib-based implementation, saving me from working out the various corner cases.

Some deserialization micro-optimizations

The next thing I worked on were some further optimizations motivated the serialization_benchmark. To recapitulate, it is a trivially simply application which just serializes a struct (OneOfEach from DebugProtoTest.thrift to be precise) to a TMemoryBuffer and then reads the data back into the struct again, repeating both parts a number of times to be able to get meaningful timing results. Here are my related changes:

-

First, I replaced

TMemoryBufferwith the newTInputRangeTransportto avoid copying the data on each iteration of the reading loop. Because the initial copying to the memory buffer took only ~1–2% of the overall time anyway, this didn’t have a great speed impact. -

The next change was to provide a shortcut version of

TTransport.readAll()forTInputRangeTransport(andTMemoryBufferas well). Previously, the genericTBaseTransportversion which just callsread()in a loop was used – because the method is called about 50 times per reading loop iteration, replacing it with a simple slice assignment gave a ~20% speedup on the reading part of the serialization benchmark. -

Furthermore, I nuked the protocol-level »read length« limit implemented for the Binary and Compact protocols. This was not much from an optimization perspective as simply due to the fact that limiting the total amount of data read really belongs at the transport level in my eyes (it was only present because of a, uhm, misguided attempt to draw inspiration from the Java library). Incidentally, this gave another ~15% speedup in the reading benchmark. I will add support for limiting the container and string size Really Soon™ (just as for C++, to be able to somehow cap the amount of memory allocated due to network input), but one more branch per container/string read should have a negligible performance impact.

-

Finally, I removed a few instances where memory was unnecessarily zero-initialized (only to be completely overwritten later) in the reading code. For the integer buffers (used for byte order conversion) this gave a small but measurable (<5%) performance boost, and for the binary/string reading (which is both larger in size and exercised more often during the benchmark) another ~8% speedup.

Profiling results

So, after all these (de)serialization micro-optimizations (I improved the writing part when first working on performance), how does the D implementation compare to its natural competitor, the C++ one? Well, frankly not too well at this point. Before discussing my findings in more detail, the performance results as measured on an x86_64 Arch Linux VM1, hosted on my MacBook Pro (Intel Core i7-620M 2.66 GHz, OS X 10.6), by running each part 10 000 000 times and averaging over it (the results are in 1 000 operations per second, so both implementations can perform on the order of a million reads/writes per second):

| Writing / kHz | Reading / kHz | |

|---|---|---|

| DMD v2.054, -O -release -inline | 2 051 | 1 170 |

| GCC 4.6.1, -O2 | 4 624 | 2 053 |

| GCC 4.6.1, -O2, templates | 5 667 | 4 509 |

The first GCC row shows the result of the vanilla build (what you get by simply doing cd lib/cpp/test; make Benchmark; ./Benchmark), while for the »templates« row, I added the (undocumented?) templates flag to the generator invocation (thrift -gen cpp:templates), which causes the struct reading/writing methods to be templated on the actual protocol type, much like what I implemented for D. In this benchmark, eliminating any indirections naturally has a huge impact on the performance.

So, why has the D version less than half the throughput for writing, and is almost four times slower on reading? Let me first point out that the actual code for the C++ and D implementations is, from a semantic point of view, virtually the same (with the exception of D using garbage collected memory for string/binary data). I think I have arrived at a point where the single largest factor influencing the performance of the serialization code is the compiler used, or to be more exact, how well it optimizes the code.

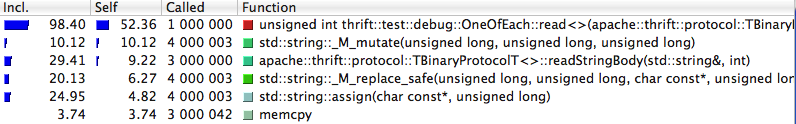

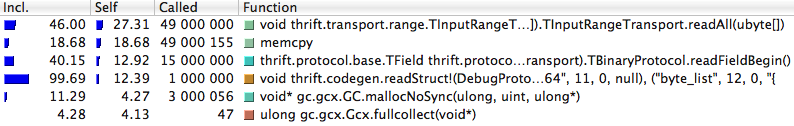

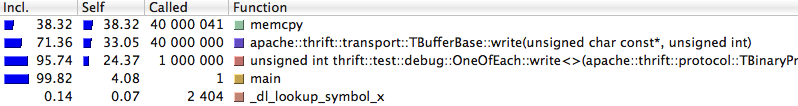

What follows are a few result from my profiling sessions (Valgrind 3.6.1, visualized using KCachegrind2) which corroborate with my assumption that compiler optimizations are the culprit here. Let’s first have a look at the profiler results for the reading part of the benchmark (this time, the loops were run only a million times each):

I only included the top six functions (by time spent in them) here for the sake of brevity, but for both implementations, the »long tail« of calls in the flat profile are actually runtime helper functions, mostly startup initialization code and memory management-related things used for reading the string functions (for D, GC calls show up prominently, because the benchmark allocates three million strings, which triggers almost 50 collections in between).

This also means that the compiler has done a pretty good job at combining all tiny deserialization functions into the top-level struct reading function by inlining – with one glaring difference: DMD chose not to inline TInputRangeTransport.readAll(), which is ultimately called when deserializing each and every member to read the actual bytes off the wire (or in this case, from memory), thus yielding to 49 million additional function calls. To make matters worse, this also means that the number of bytes requested each time (e.g. 4 for an integer) is not known at compile time, which also means that the generic memcpy implementation has to be called each time. On the other hand, the C++ implementation only calls memcpy in those situations where the number of bytes copied really depends on a runtime value, which is the case for strings which are intrinsically variable-length (the other memcpy calls are called during initialization and initially writing the struct to the buffer).

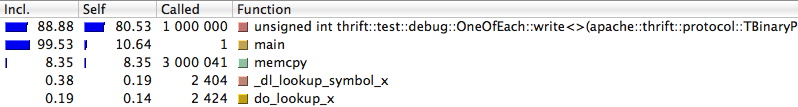

Profiling the writing part shows similar results:

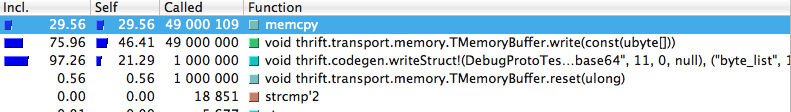

Again, for the C++ version, everything is inlined into OneOfEach.write(), in which over 80% of the time are actually spent, and just as for the reading part, the only instance where memcpy() is not inlined3 is for strings. On the other hand, the D version is optimized almost as well as the C++ version, with the only exception of TMemoryBuffer.write() not being inlined, which again prevents memcpy from being optimized (the other function showing up, reset(), only resets output buffer once per iteration, this is inlined into main in the C++ version).

So, to recapitulate, I am not sure whether DMD would be able to replace a memcpy() call with optimized asm in the first place, but not knowing the length at compile-time prevents that anyway. I am pretty sure that this difference of about a hundred million function calls and not being able to write optimized text for the short (2, 4, 8, …) byte copies accounts for a large part of the performance gap.

This assumption is supported by data gathered from a case where GCC chose to not inline TBufferBase::write() (which is the common path of TMemoryBuffer::write()). Interestingly, this actually happens at -O3, which is a higher optimization level than -O2 used above (I suppose because of some additional optimizations performed on it, which causes its inlining costs to rise high enough not to be inlined). Just for comparison, here are again the five top functions from the profile:

-O3, causing TBufferBase::write() to be no longer inlined.Just as for D, because of this memcpy cannot be optimized away either. And unsurprisingly, this causes the performance to go through the floor as well, the executable only reaches 2 519 thousand operations per second now. The D version is still a bit slower with only 2 051 kHz, but it is on a comparable level now.

So, to finally come to a conclusion, most of the performance gap between C++ and D presumedly comes from DMD not inlining a key function and thus not being able to optimize away memcpy calls as well. An obvious experiment would be to try a different compiler like GDC or LDC, both of which are known to generally optimize better than DMD does. Unfortunately, both of them are currently at front-end version 2.052, but my Thrift code currently requires 2.054.

There are two possible solutions to this, either sprinkle workarounds all over the Thrift code to be able to use the older DMD frontend and Phobos versions for the benchmark, or update the frontend of GDC or LDC to 2.054. While the former would be entirely feasible, I think I update the LDC frontend once I have some time to spare, as this will also be useful for other D projects (choosing LDC because I am already familiar with its codebase).

Libevent-based non-blocking server

If I didn’t lose you during all the talk about micro-optimization above, let me hereby present you the two main additions to the library during the last two weeks: a non-blocking server implementation and a Future-based asynchronous client interface.

I am not sure if I ever stated it explicitly (the timeline only has »event-based I/O Phobos lib?« in parentheses), but I was hoping to be able to come up with a small general-purpose non-blocking I/O library written in D as a by-product of this project. The obvious time to start working on it would have been when implementing the non-blocking server, But after considering several possible designs, I realized that I did not yet know the problem domain well enough to come up with something that is not just a cheap libevent/Boost.Asio rehash, but where I’m still sure that it performs well enough for a production-grade Thrift server implementation.

Thus, I went with simply porting the C++ libevent-based server implementation over to D, which has the benefits of being battle-proved, so that I have something which I can advise people to use in production code without feeling guilty. There are a few instances where I needed to manually add a GC root for some memory passed to libevent, but other than that, the code is reasonably clean, even though it surely could be prettier if a native D »event loop« was used.

A word of warning for Windows users: While libevent is linked dynamically as well, thus making it easy to just use DLL builds on Windows, there are some pieces of the socket code not yet tested for WinSock. Currently, I am not even sure if all of the code compiles on Windows, but I will perform some test on Windows shortly to ensure all the new additions work there as well.

Coroutine-based TAsyncClient

Using an asynchronous/concurrent approach for network-related code with its intrinsic I/O latency seems like a very obvious thing to do, but to my knowledge e.g. the C++ libraries currently do not provide a generic async client implementation, which is the part of the reason I did not tackle this earlier.

After getting accustomed with the general idea of non-blocking I/O, it seemed to be a good time to finally work on the topic. What I basically wanted to implement was a way to off-load client-side request/response handling, possibly for multiple connections, to a worker thread, providing a future-based interface to the client code. For multiplexing handling multiple connections per worker thread, I wanted to experiment with a coroutine-based design.

As mentioned in the beginning of this report, coming up with a solid design took me a bit longer than expected, but as of now, thrift.codegen includes a fully functional TAsyncClient implementing such a scheme, also using libevent to have a portable means for handling non-blocking I/O. The new thrift.async package contains the related helper code, such as TAsyncSocket representing a non-blocking socket.

The new code is not yet well-documented or tested, and is still missing some important features like the ability to set timeouts on operations, but I have successfully tested basic use cases.

Plans for the second GSoC half

Which finally brings me to the end of this post: As my project fortunately passed the mid-term evaluations, it is now time to discuss how to go forward during the second part of the Summer of Code.

During the next week, I will work on some of the obviously unfinished things like async client documentation and tests, and will add a few missing utilities such as a tee-like transport which can be used to transparently log requests.

Speaking of documentation, this currently is a big issue for both the D implementation and, to a lesser extent, Thrift in general. However, as of now, I have worked sufficiently long on the code that I am effectively blind for what kinds of documentation a typical user would benefit the most from – more detailed API docs? Simple stand-alone examples with well-commented code? Tutorials? It would be great if you could let me know what you think would be useful.

With the non-blocking server implementation being completed, only the »performance« and »documentation« items from my original timeline remain, besides some general clean-up work being left to do. However, Nitay, my mentor, suggested a few other things which could be worth looking into, such as a generalized client for querying multiple servers, to be used for things like redundancy, load distribution, data verification, etc. I will discuss this in more detail and then update the timeline accordingly.

1 Why test in a Linux VM (Virtual Box 4.0.8) rather than directly on my OS X development box? Because Linux x86_64 is probably where most of the server-side deployments will end up, only an ancient GCC is available on OS X, DMD is still 32 bit-only there, and Valgrind/Callgrind which I used for profiling is not really usable on OS X 10.6. I am aware that using a VM might skew the results a bit, but I think the impact shouldn't be too large. Incidentally, the tests compiled and ran in the Linux VM generally performed better faster than on the host.

2 I patched KCachegrind to elide the middle of the symbol name for better readability in width-limited screenshots, and used my own little demangling tool for the D results.

3 Technically, GCC handles memcpy as compiler built-ins, so inlining might not be precisely the right term, but the effect (avoiding a function call) is the same.